Indian Temple Complex, Tamil Nadu:

India is a country that never fails to amaze me. I have been lucky enough to travel the length and breadth of this beautiful, enormous country and have a lifetime of memories. Highlights include trekking in the mighty Himalaya, snorkelling in the seas off Goa, hurtling through the thronging streets of Calcutta, Delhi and Bombay in an auto-rickshaw, an early morning boat cruise along the ghats in Varanasi, and glimpsing tigers in Ranthambhore National Park. However, it is the South of India that has captured my heart.I love the lush, tropical greenery of Kerala with its warm, friendly people, delicious food and laid-back lifestyle. Whether floating down the delightful canals and waterways in the backwaters on a converted rice-barge or sampling the local tea around Munnar it is hard to imagine a more enjoyable place to be. In comparison to Kerala, the state of Tamil Nadu has made a relatively small impact on the world of tourism.

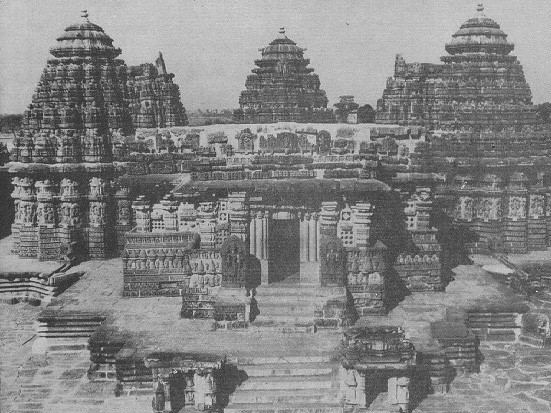

Indian Temple Complex, Tamil Nadu

However, it is certainly not short of attractions for those travellers wishing to escape the well-worn tourist trails of Rajasthan and Kerala. Famed for its ancient temples and detailed rock carvings, Tamil Nadu is a state steeped in tradition. Religion is taken very seriously here and pilgrims pour into the ancient sites of Kanchipuram, Chidambaram, Trichy, Tanjore and Madurai in numbers far exceeding the numbers of tourists visiting these sites. The temple architecture is fascinating; from the brightly coloured and steeply stepped gopurams such as those in Madurai, to the 7th century rock-hewn temples in Mahabalipuram. There is, however, more to Tamil Nadu than just temples, temples, temples.

The area collectively known as Chettinad is an extraordinary blend of rural Indian life and majestic Chettinadu mansions that hark back to a former, more glorious time. These houses are built using Burma Teak, beautiful local tiles, and Italian Marble and have spacious courtyards and large high-ceilinged rooms. On a guided tour it is possible to visit some of these mansions, as well as see local artisans at work producing tiles and pottery, and visit small, rural villages.

The palace in Chettinad is a delightful blend of architectural styles and although predominantly white has some wonderful splashes of colour as well. So wonderful is the palace in fact that Ms. Amrita Gandhi (great-grand-daughter of Mahatma Gandhi) was staying there whilst filming a television series in the area! My colleague Daniel and I were lucky enough to make her acquaintance. Pondicherry is steeped in French influences and is a fascinating place to visit during a journey through Tamil Nadu. Highlights include beautiful French architecture, a windswept promenade, fabulous shopping opportunities, and Auroville, described as an experimental township conceived as ‘an alternative exercise in ecological and spiritual living’.

Locals, Tamil Nadu

One of my favourite things to do in Pondicherry is eat dinner at the rooftop restaurant at The Promenade hotel. The food is delicious and the cooling sea-breezes and sound of the waves make for a wonderful dining experience. A journey through Tamil Nadu truly is an eye-opening and memorable experience and one that is only heightened by the incredible warmth and vitality of the Tamil people.”

2.

Thoniappar Temple at Sirkali near Chidambaram in Tamilnadu

Almost all Indian art has been religious, and almost all forms of artistic tradition have been deeply conservative. The Hindu temple developed over two thousand years and its architectural evolution took place within the boundaries of strict models derived solely from religious considerations. Therefore the architect was obliged to keep to the ancient basic proportions and rigid forms which remained unaltered over many centuries.

Even particular architectural elements and decorative details which had originated long before in early timber and thatch buildings persisted for centuries in one form or another throughout the era of stone construction even though the original purpose and context was lost. The horseshoe shaped window is a good example. Its origins lie in the caitya arch doorway first seen in the third century B.C. at the Lomas Rishi cave in the Barbar Hills. Later it was transformed into a dormer window known as a gavaksha; and eventually it became an element in a purely decorative pattern of interlaced forms seen time and time again on the towers of medieval temples. So, in its essence, Indian architecture is extremely conservative. Likewise, the simplicity of building techniques like post and beam and corbelled vaulting were preferred not necessarily because of lack of knowledge or skill, but because of religious necessity and tradition.

On the other hand, the architect and sculptor were allowed a great deal of freedom in the embellishment and decoration of the prescribed underlying principles and formulae. The result was an overwhelming wealth of architectural elements, sculptural forms and decorative exuberance that is so characteristic of Indian temple architecture and which has few parallels in the artistic expression of the entire world.

It is not surprising that the broad geographical, climatic, cultural, racial, historical and linguistic differences between the northern plains and the southern peninsula of India resulted, from early on, in distinct architectural styles. The Shastras, the ancient texts on architecture, classify temples into three different orders; the Nagara or ‘northern’ style, the Dravida or ‘southern ‘ style, and the Vesara or hybrid style which is seen in the Deccan between the other two. There are also dinsinct styles in peripheral areas such as Bengal, Kerala and the Himalayan valleys. But by far the most numerous buildings are in either the Nagara or the Dravida styles and the earliest surviving structural temples can already be seen as falling into the broad classifications of either one or the other.

In the early years the most obvious difference between the two styles is the shape of their superstructures.

Jagadamba Temple at Khajuraho in Madhya Pradesh

The Nagara style which developed for the fifth century is characterized by a beehive shaped tower (called a shikhara, in northern terminology) made up of layer upon layer of architectural elements such as kapotas and gavaksas, all topped by a large round cushion-like element called an amalaka. The plan is based on a square but the walls are sometimes so broken up that the tower often gives the impression of being circular. Moreover, in later developments such as in the Chandella temples, the central shaft was surrounded by many smaller reproductions of itself, creating a spectacular visual effect resembling a fountain.

From the seventh century the Dravida or southern style has a pyramid shaped tower consisting of progressively smaller storeys of small pavilions, a narrow throat, and a dome on the top called a shikhara (in southern terminology). The repeated storeys give a horizontal visual thrust to the southern style.

The colossal Periya Kovil (The Big Temple) at Thanjavur, Tamilnadu

Less obvious differences between the two main temple types include the ground plan, the selection and positioning of stone carved deities on the outside walls and the interior, and the range of decorative elements that are sometimes so numerous as to almost obscure the underlying architecture.

Bearing in mind the vast areas of India dominated by the ‘northern’ style, i.e. from the Himalayas to the Deccan, it is to be expected that there would be distinct regional variations. For example all of the following are classified as Nagara - the simple Parasuramesvara temple at Bhubaneswar in Orissa, consisting only of a shrine and a hall; the temples at Khajuraho with their spectacular superstructures; and the exquisitely carved Surya temple at Modhera. On the other hand the ‘southern’ style, being restricted to a much smaller geographical area, was more consistent in its development and more predictable in its architectural features and overall appearance.

In the border areas between the two major styles, particularly in the modern states of Karnataka and Andhra Pradesh, there was a good deal of stylistic overlap as well as several distinctive architectural features. A typical example is the Hoysala temple with its multiple shrines and remarkable ornate carving. In fact such features are sometimes so significant as to justify classifying distinct sub-regional groups.

Hoysala style temple from Hailbedu, Karnataka

The type of raw materials available from region to region naturally had a significant impact on construction techniques, carving possibilities and consequently the overall appearance of the temple. The soft soap-stone type material used by the Hoysala architects of the twelfth and thirteenth centuries allowed sculptors working in the tradition of ivory and sandalwood carving to produce the most intricate and ornate of all Indian styles. Hard crystalline rocks like granite typical of the area around Mamallapuram prevented detailed carving and resulted in the shallow reliefs associated with Pallava temples of the seventh and with centuries. In areas without stone, such as parts of Bengal, temples constructed of brick had quite different stylistic characteristics.

Royal patronage also had a very significant effect on the stylistic development of temples, and as we have already seen, regional styles are often identified by the dynasty that produced them. For example we speak of Pallava, Chola, Hoysala, Gupta, Chalukya and Chandella temples.

It might be assumed that temple styles would be different for the various Hindu cults. In fact, this was never the case in India. Even Jain temples such as those at Khajuraho were often built in almost identical styles to the Hindu temples.

From the eighth century onward with the development of ever more sophisticated rituals and festivals, the Hindu temple especially in the south started to expand and become more elaborate. There were more mandapas for various purposes such as dancing, assembly, eating, or, for example. To house Nandi, Shiva’s sacred mount; more subsidiary shrines and other structures; and more corridors and pillared halls such as the ‘thousand-pillared halls’.

But the most significant visual difference between the later northern and southern styles are the gateways. In the north the shikhara remains the most prominent element of the temple and the gateway is usually modest. In the south enclosure walls were built around the whole complex and along these walls, ideally set along the east-west and north-south axes, elaborate and often magnificent gateways called gopurams led the devotees into the sacred courtyard. These gopurams led the devotees into the superstructures and capped with a barrel-shaped roofs were in fact to become the most striking feature of the south Indian temple. They become taller and taller, dwarfing the inner sanctum and its tower and dominating the whole temple site. From the Vijayanagara period (fourteenth to sixteenth century) onward, these highly embellished and often brightly painted structures become extremely numerous. The width of the storeys of pavilions and other architectural elements were carefully adjusted to create a concave contour which is a distinctive characteristic of the Dravida temples seen throughout the south, particularly in Tamil Nadu.

An example of a fully developed temple built between the thirteenth and seventeenth centuries is the Ranganatha temple at Srirangam. Eventually it became, in fact, a temple-city with 21 gopuras and 7 enclosure walls surrounding 156 acres. Each encircling space is less sacred the further one moves away from the garbhagriha. The outer three enclosure walls contain shops and houses for 50,000 people to carry out their normal business. The plan is an example of the concept of the cosmos as a series of concentric rings around the God. Clearly not only the temple but the whole city has been conceived as a mandala.

3.

Terms like feet, legs, thighs, neck and head denote the anatomical position and function of the structural parts corresponding to those of the human body, and are often used figuratively to emphasise the concept of organic unity in temple architecture.

Terms like feet, legs, thighs, neck and head denote the anatomical position and function of the structural parts corresponding to those of the human body, and are often used figuratively to emphasise the concept of organic unity in temple architecture.

.

.

The architectural origins of the several parts of the temple are significant. The base is derived from the Vedic sacrifical altar, the plain cunbical cell of the sanctum from the prehistoric dolmen, and the spire from the simple tabernacle made of bent bamboos tied together to a point.

The sanctum with its massive walls and the dark interior represents a cave, while the superstructure with its peak-like spire-the shikhara-represents a mountain and is frequently designated as the mythical Meru, Mandara, or Kailasa

0 Comments:

Post a Comment